by Jim Lane

Note. This is Part 2 of our series on the inside true story of KiOR.

In part 1 of our series, here, we explored: the formation of BIOeCON and KiOR, the problem of too much oxygen and coke, the entry of Khosla Ventures, and the loss of a CEO. Also, “a recipe for technical failure”, disastrous pilot scale results, culture clashes, catalyst development, reactor design trouble and the departure of a key scientist.

Two KiOR scientific wings emerge

No one was more emphatic about the pilot plant results than scientist Robert Bartek, who sent an email ‘More Math on BCC’ on December 7th, stating:

“We are in a period of denial. We must forget that our original conceptions of BCC are not right and must do something radically different to save the Project”.

By the end of 2008, it is clear from discussions with multiple KiOR sources that the KiOR scientific staff had divided into two groups. One group believed that the BCC Technology had been sufficiently tested, was not working, had no value to KiOR’s business and should be immediately stopped.

The other group, which was headed by O’Connor, focused on improving the BCC Technology, and on support of the three European Labs doing so. The controversy over the R&D Plan for 2009/2010 to the extent that it exacerbated a growing rift between O’Connor and Ditsch would have far-reaching consequences as 2009 unfolded.

Paul O’Connor confirmed that cultural problems were rife at KiOR at this point.

“Part of this was my problem because I wasn’t there full time in Houston,” O’Connor told The Digest. “Basically I was the CTO, and André [Ditsch] had no experience in FCC biomass or hydrotreating, but he had it in his head that he was second in command to Fred. When I was away he would push it in another direction. Because people considered him Samir’s boy [Samir Kaul, a partner in Khosla Ventures], and no one dared to criticize him much. I did, and that became a problems.

“Partly, that was the Houston culture. In The Netherlands as in places like San Francisco and New York, everyone tells you exactly what they think of you even in the management meeting, we fight like crazy but we resolve issues and make up. In Houston, people don’t often want to talk about the problem. It’s a case of everything is fine, everything is great, and Fred was very good at that.

“But there were problems to be solved, and there would be all these in-fights between myself and Ditsch, and with so many new people. Everyone wants to invent their own process and thinks they have the right ideas. Fred never really took a stand, he always stayed out of it.”

No team, no stable technology

“One problem that hurt KiOR,” O’Connor recalls, “was we just had too many people from Albemarle. Catalysis is important, but what we needed also were process engineers, and people with experience in hydrotreating and operations. The balance went wrong.

“And then there was this entirely different idea, coming I suppose from the Khosla approach to business, and André himself in some ways represented this approach, which was to go out and hire a whole bunch of MIT PhDs. But you need time to train them and they are not the ones who are going to scale up a process.

“And so it became a struggle to unite all these people into one team, and in that struggle I began to struggle with Fred, and it became a case of Fred and André on one side, and although I stayed around until the end of 2009 my influence was minimized.”

By all accounts, at the beginning of 2009, as one source familiar with the state of technology development described it, “KiOR had no Technology that was sustainable, competitive, cost-effective, and economically/technologically feasible, and the operating funds were practically depleted.”

By all accounts, at the beginning of 2009, as one source familiar with the state of technology development described it, “KiOR had no Technology that was sustainable, competitive, cost-effective, and economically/technologically feasible, and the operating funds were practically depleted.”

The fateful Columbus first commercial-scale plant

A Stealth Team forms

Amongst the loosely-associated group of staff that felt the BCC technology as designed was hopeless, a “save the company” effort launched on a stealth basis.

Their goal? Reliable, data showing increased bio-oil yields of reasonable quality using less costly catalysts and processes. The new data, demonstrating a feasible technology, could be used by KIOR in business development, and to convince new investors in funding efforts.

The timing? Those who were aware or active in this effort took the view that time was critical, not only because KiOR, as a company in development, was shortly going to be starved for funds if results were not forthcoming; they were also concerned that the plans and design of the demonstration-scale Unit (a 10 ton/day biomass processing capacity) needed to be formulated, firmed and contracted out for fabrication. And any new technology would need to be developed before that.

Out of a wider group, catalyst expert Mike Brady, FCC unit expert Robert Bartek, solid state chemistry expert Dennis Stamires, and Drs. Vasalos and Lappas of CPERI in Greece would be the most visible. Their concern was not only the development of a technology that could save KiOR from disaster, but doing so in a way and in a time frame that would not cost them their own jobs.

In February 2009, Stamires wrote to a scientific team composed of Bartek, Yanik, Loezos, Cordle, and Brady, proposing that, at the KiOR Pilot Plant, test runs to duplicate published test data obtained from other similar Pilots using the same biomass feed and sand as a heat transferring medium. This was the baselining project which had been specifically ruled out for the KBR pilot.

Paramount the need to ascertain why the CPERI FCC Pilot Plant produced higher bio-oil yields than the KiOR pilot. The Stealth Team decided to conduct a “Round-Robin” testing program where both Pilot Plants would use the same biomass feed, sand/catalyst and process conditions.

The idea?

Stamires reasoned that, if Prof. Vasalos and Dr. Lappas at CPERI , who had a similar FCC Pilot plant in operation, could pyrolyze the same kind of biomass with sand, under the same process conditions, the team could confirm that new KiOR pilot was working correctly. If the CPERI FCC Reactor design was responsible for the higher Bio-oil yields, then the design could be introduced into the KiOR Pilot.

On the same day, Bartek replied: “I agree! I am hoping we can do significant alterations to the process to assure some chance at victory in the next two months, so we do not purchase the wrong DEMO“.

After baselining the pilot plant, the expectation was that new catalysts could be tested aimed at improving bio-oil yields. Specifically, Bartek speculated that it was “Time for some Z?”

Meaning “ZSM-5 catalyst”. A commercial grade, high-priced catalyst, well established in the market place, being used by most oil refineries worldwide, containing the ZSM type of Zeolite. Papers had been published by Dr. Paul Williams at Leeds University in 1995 indicating that zeolite catalysts would not produce a high bio oil yield, but could produce, as one observer put it, “a reasonable amount with a substantially improved quality containing a lesser amount of oxygen, ea

sier and less costly to be upgraded to gasoline and diesel fuels.”

Whose technology is this, anyways?

The other team? In a March 5th memo to the KiOR community, a R&D review of the BCC Technology, specified the continuation of the R&D work on BCC Technology in all four Labs.

As O’Connor confirmed to The Digest, “one of my biggest frustrations was that the technology that was moving forward was never actually the BIOeCON technology. What we were doing in Valencia was not what we did later in Houston. If you look at the first patents and so on, you see that the basic trick was to have an interaction between the biomass and the catalyst before it enters into the reactor. We called it mechano-chemistry. When I compared the data between Houston and Greece, Greece was better, and that was because in Houston, they never pre-treated the biomass.

“That created more conflict with Ditsch. He had a ‘make it simpler, don’t do that’ attitude towards it. And you could sort of get away with it in the pilot plant because you could mill the biomass very fine. But when you get to demo scale, much less commercial, you can’t mill the biomass like that. For one, it can get sticky. It can even catch fire in the plant, which happened.

“But if you are feeding [larger] wood particles of 1-3 MM instead of this finer sort, it takes quite a long time before the particles heat up, and the outside can get charred while nothing happens to the inside.”

So you coke up and lose yield.

Cannon sidelined by heart problems, and “who’s in charge?” chaos ensues

But the week of March 8th would prove even more fateful for KiOR, as CEO Fred Cannon was hospitalized with a heart problem and was sidelined for some weeks, in hospital or at home, while recuperating.

And so, a leadership crisis erupted.

By March 19th, O’Connor emailed the staff, “In the absence of Fred, I have assumed his responsibilities to assure a smooth continuation of our business.” Most staff at the time took that to mean that, as soon as Cannon returned to the office, O’Connor would assume his former duties.

But more than that was going on.

Cannon had received a memo from O’Connor, expressing concern about the leadership of KiOR, the direction KiOR was taking, and a lack of team effort and communications between groups. O’Connor expressed the view that, if matters continued as they were, key personnel would leave the company.

Some discussions took place over a potential revision of management duties and structure, which failed, not the least because as Cannon explained, even if he really wanted to re-divide CEO responsibilities and authority, he could not do that without a resolution and approval by the KiOR Board.

A degree of chaos ensued, and morale dropped. In Cannon’s absence, VP for Strategy Andre Ditsch also stepped forward to assume more commercial responsibility, and it became at times unclear to staff who was in charge.

One observer recalls, “[Ditsch and O’Connor] were calling their own regular staff meetings at the same time, and starting to re-organize and re-assigning responsibilities and projects to the staff.”

The controversy over the research program boiled over. Those familiar with this period at KIOR said that Ditsch “accused O’Connor of grabbing for Cannon’s job”, and having failed to develop a feasible technology, despite two years of investment in R&D.

The battle reached the KiOR board in March 2009. The board confirmed Cannon as President and CEO of KiOR, Ditsch remained VP for Strategy; in May 2009 O’Connor was re-assigned from the CTO role, although he continued to work for KiOR until November 2009 when his contract expired.

Observers of KiOR during this period stress that, although Cannon returned to the office by the end of March, Andre Ditsch assumed some extra managerial functions and, according to one observer, “was communicating frequently directly with Samir Kaul (a KiOR Board member, representing Khosla).”

Dead Man Walking

While the management crisis was unfolding, the Stealth Team had outlined new catalysts and had made the request to test these, and to calibrate the KiOR pilot plant with sand. The request ultimately would have to be made to Ron Cordle, the Pilot Plant supervisor, as a confidential, weekend test. The backup plan was to have CPERI run the tests in their pilot in Greece.

“It was like the blind leading the blind,” Stamires recalled. “The KiOR pilot plant reactor was deficient and underperforming and not capable of producing optimum bio-oil yields. Adding to this structural Reactor problem, and [later] the additional problem of the data manipulation of John Hacskaylo. The combination of these problems resulted in a general situation where nobody knew what we were actually doing, what oil yield numbers to believe.”

As Robert Bartek would express in a March 28th memo:

“You had already been hounding me to get sand in the Unit. At that time the three of us started on this, I had already accepted the fact that I was a “Dead Man Walking” in Fred’s organization and my time at KiOR would be short. So why not one final act of defiance? If you are going to be let go, let’s do it for a noble project reason rather than politics. May be we could rescue this thing and snatch victory out of defeat we [are] heading into.”

Ultimately, the sand test was carried out, using sand obtained from CPERI, and confirmed that higher oil yield was produced at the Pilot Plant at CPERI in Greece. That finding prompted Bartek and Stamires with further discussions with Lappas and Vasalos, to arrange a meeting with Cannon and Vasalos in Houston. And an agreement was made with Cannon that CPERI would license the design of their Reactor to KIOR

With this, the Reactor at KiOR’s Pilot was replaced with a new Reactor constructed according to the design of the CPERI Pilot Plant. With some process variables optimizations, the KiOR Pilot Plant was able to produce higher Bio Oil yields.

Work on catalysts also continued. The Stealth Team was convinced by that time that the BCC Catalyst (the synthetic clay) was a very poor heat conductor, and incapable of transferring a sufficient amount of heat to the Biomass fast enough. They thought that a new material with high bulk density, low porosity microspheres, with a low catalytic activity, would be much more suitable.

By March 9th, the Stealth Team had obtained, via “a friend at BASF”, 5 gallons of high temperature calcined clay microspheres, which were tested secretly at the KiOR Pilot Plant. In a memo on March 27th, Bartek reported to O’Connor, Yanik and Stamires an overall substantially improved performance over the BCC Technology and its Catalyst. Oil yields were higher, there was less coke, and a reasonably low oxygen content in the oil. The Stealth Team began to make arrangements to purchase a Spray Drier and a Calciner to be able to make calcined clay microspheres.

Meanwhile, a March 13th 2009 report from Peter Loezos entitled Mass Balance Data “validated again that BCC technology was not working for KiOR,” an observer reported. Dennis Stamires added, “It was mainly due to the very low bio-oil yields.”

Stamires also pointed The Digest to an independent validation of the performance of the HTC catalyst (i.e. the Hydrotalcite, HTC), published in 2013 in the Defect and Diffusion Forum by F. L. Mendes, A.R. Pinho, and M.A.G Figueiredo. That report concluded:

“The use of either the FCC catalyst or hydrotalcite are not suitable for intermediate pyrolysis reactors, generating a product with high water content and low content of organic compounds in bio-oil and produce more coke. None of the materials tested produced bio-oils with considerable hydrocarbons yields and presented high amounts of phenolic compounds. In general, silica had the best resu

lts in terms of yield and quality of bio-oil.”

Both Mendes and Pinho were working for Petrobras in Brazil, and during this period it has been asserted to The Digest that KiOR was involved in negotiations with Petrobras, regarding forming a joint venture, or licensing KiOR’s BCC Technology. Suggesting though not proving that the journal results reported were related to KiOR story.

The Tipping Point

By April 2009, Cannon had returned to his desk at KiOR, but according to an observer, for some time after Cannon returned, “In reality, it was Ditsch and [Kaul] who were managing KiOR, and Cannon seemed to be a bystander, and sometimes their spokesman.”

One notable change in the company’s management style? “Most of the important and crucial issues were only discussed in the new mini-Management Team of Ditsch and Cannon, in communication with Samir,” one team member recalled. “Not in the weekly general management team meetings as was done before.”

The problems facing KiOR at the time were substantial, but not unheard of for a young company in the advanced bioeconomy. They were summed up internally at this time as:

*Finding new investors to provide further funding as KiOR was soon running out of monies.

*Having not yet developed and demonstrated a feasible, sustainable and profitable technology, it was difficult to convince new investors to provide funds for KiOR’ operation.

*Soon running out of monies, will be difficult to keep the R&D function going on, which was needed to develop new sustainable technology.”

*The large processing capacity Demonstration Pilot Plant Unit (DEMO Unit ) was being designed and will require several millions of dollars to be constructed and installed at the Houston KiOR site.

*Negotiations were going on with Chevron / Weyerhaeuser/Catchlight Energy, involving the formation of a joint venture, in which KiOR will provide the technology to convert waste wood to liquid fuels. However at that time, KiOR did not have technology that was sustainable and commercially feasible and profitable.

*KiOR was in a great need to have a feasible demonstrated technology which can be commercialized and be economically sustainable and profitable, for use in the discussions and application to the DOE for getting a loan guarantee of a $1 billion, for use in building commercial Plants.

*KiOR was in need to have, at pilot plant / DEMO Unit scale, its Technology demonstrated and validated that was feasible, economically sustainable and profitable, while discussing with the Mississippi Development Authority a $75 million loan.

*Morale of KiOR’s employees was very poor with a fragmented Management leading in different directions, while key technical personnel, either had left or were looking for new jobs outside KiOR.”

*KiOR’s competitors Ensyn and Dynamotive were fast developing and improving their technologies, and preparing for commercialization.”

65 gallons per ton, but not really

It was this latter point the progress of Dynamotive, that perhaps formed a tipping point in the story of KiOR.

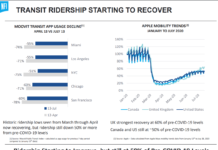

For, coincidentally or otherwise, we see the first appearance of 60+ gallons per ton yields, a level of yield that would eventually feature prominently in KiOR’s 2011 IPO, in an analysis written by Andre Ditch not of KiOR’s results, but of Dynamotive’s.

Ditsch was juggling at haste data from Dynamotive and results from a UOP/PNNL project as reported in the September 2008 issue of Hydrocarbon Processing, written by a team led by Jennifer Holmgren (nowadays, CEO of LanzaTech), then GM of UOP’s Renewables unit, entitled “Consider Upgrading Pyrolysis Oils into Renewable Fuels”. He notes that he is “running out of daylight for report, but a few comments”.

Later, he comments “IF (big if) we assume the UBA oil and our Kaolin oil are similar (without more data, a stretch)…”. Later still, he added that “all this is written in great haste, so feel free to add and pressure test numbers.” All indicative of a memo written in back-of-envelope calculations.

Overall, Ditsch projected a break-even for KiOR at a yield of 65 gallons per ton of biomass, or a 22.5% yield of bio-oil from the biomass.

From this point forward until the end of 2013, it will be impossible to find a commercial projection or communication based on less than 60 gallon per ton yields, or a scientific set of data from any KiOR pilot, demonstration or commercial unit that has a yield of 50 gallons per ton or higher (even at an oxygen content of 17% that would be very difficult to upgrade).

Exotic yields get mentioned like “business as usual” scenario baselines in this KiOR slide presentation.

“We need 2X”

By June 2009, the Stealth Team, working with zeolite catalysts in the Pilot Plant, were showing enhanced yields and bio-oil quality. At the same time, literature searches turned up projects from the 1980s and 1990s demonstrating that the same type of Zeolite (ZSM) had been used before in Catalytic Pyrolysis.

But with the improvement, KiOR yields approached a maximum of 40 gallons per ton with reasonable quality. “Higher yields would have been simply contained more oxygen, that would have needed to be removed to convert the bio-oil to transportation fuel,” Stamires told The Digest.

A progress update was held on June 3rd with Khosla, Samir, Cannon, Ditsch, O’Connor and others, Bartek reported the figures.

Khosla’s response was to request of the R&D team that they double the yields over the next 6-8 months. The improvements were not from outer space. They were the kind of yields that would have made the overall process economically sustainable and profitable, without government subsidy, in commercial-scale plants. A participant in the meeting reported to The Digest that certain milestones for monthly incremental increases were established to reach the target.

Possible? Yes. With the existing BCC technology. In the view of one wing of KiOR’s staff, no. Given management’s reluctance to change the R&D plan, add a reactor to the process, hire scientists who could accomplish these goals, numerous members of the scientific team were pessimistic both in terms of the target and the timeline.

Concerns were high, as commercial discussions with Chevron and Weyerhaeuser (as the JV Catchlight Energy) were well underway. As one team member put it, “if Chevron finds out, they will run away from KiOR and essentially seal KiOR’s fate from any future partnerships with Big Oil, and Khosla would pull his funding.”

The race for 2X gets underway

The search for catalysts was underway at a rapid pace.

Cannon approved the request of Brady, Bartek and Stamires to start making KiOR’s own calcined clay microspheres using the spray dryer. The main objective of this work was to develop clay-based microspheres which exhibited acted both as efficient heat carriers, and catalysts with controlled selective activity.

Having then optimized the Physical properties of the calcined microspheres with respect to Bio-oil yield and quality, Brady, Bartek and Stamires proceeded to optimize the chemical/catalytic properties of the calcined micros

pheres. Then Brady proceeded to prepare clay microspheres with different amounts of catalytically active metal salts magnesium, calcium, potassium, sodium, and aluminum among others.

In addition, Professor Iaocovos Vasalos re-appeared as a consultant by September 2009. Subsequently, Prof. Vasalos confirmed to Cannon that in order to achieve reproducible Bio oil Yields close to Khosla’s 2X target, with a reasonable quality, certain “radical changes must be made in the design of the pilot plant and to the process.”

The urgency was not only the usual pace of s start-up hungry for milestones that would encourage investments, there was Catchlight Energy relationship looming. In an email from Dan Strope, VP Technology, sent Aug. 11 2009 to the staff, it was revealed that Andre Ditsch was officially heading the negotiations with Chevron, and Ditsch was asking for technology data to prepare an economic forecast for a commercial size plant.

Yields improve, but trouble looms

In an email to Fred Cannon and Andre Ditsch on September 23rd, Bartek reported pilot plant data confirming that the ZSM catalysts produced much higher hydrocarbon yields, as the BCC Catalyst (HTC ) was converting them to gas and coke. The oxygen was in the range of 10 to 15%, but the yields were still stuck in the low 40s. With these results, the decision was taken in late 2009 to suspend work on the BCC technology at the three European Labs as well at KiOR’ Lab in Houston.

Paul O’Connor, still on the KiOR board at this time, blasted the decision to use ZSM-5 catalyst.

“It was the worst decision ever made, ZSM-5. We all knew that to make this process economic we needed a cheap catalyst. ZSM-5 is one of the most expensive around. Plus, you are dealing with a biomass with calcium and many other things in it, and with ZSM 5 you kill the catalyst. It’s so strange they went in that direction.”

But yields at least were up. A 20-30% jump in yields, but catalyst performance, the science team concluded, would not improve anywhere as fast as the 2X target required. In a memo dated Sept. 6, 2009, Stamires proposed a radically different Biomass Conversion system, comprising two Reactors in series or in parallel, with a new catalyst.

The approach? The Biomass in the first Reactor would be thermally Liquefied in a fluidized bed using a high-efficiency heat transferring medium which has a high heat capacity (such as sand ). The Bio oil vapors generated in the first Reactor would then be reacted with a medium activity catalyst in the Second Rector. The invention was subsequently patented by KiOR .

Meanwhile, Ditsch was pressing hard. In emails of Sept. 16 and 17, 2009, he was asking for information to be used in his presentation and “KiOR Update” to Khosla on the 17th .

From that update, Khosla agreed to relax the timeline for process improvement, but not sacrifice the yield target, which would have been in the 80s and into the 90 gallons per ton range. The 2X milestone target was set for Q4 2010. But the scientific team at least one wing didn’t believe that anything like those yields could be achieved with anything like the technology that KiOR was readying for commercial-scale.

Stuck in the 40s Doldrums

New catalyst materials were tested in KiOR’s Pilot KCR plant in October and November 2009 Bartek and reported by Patrick Steed in a January 7, 2010 email confirmed the improvement in catalytic activity, while retaining their good heat-transferring properties.

But, the good results came with a ceiling. In their own way, they confirmed to members of the science team, as sources told The Digest, that KiOR was likely to become stuck in a range which would never get much out of the 40s, expressed in gallons per ton.

2010 dawns, with a design input issue

In January 2010, though, focus was on a potential 20% bio-oil yield improvement possible by employing CPERI’s reactor design, compared to the yields obtained by the present design of the KCR Pilot plant (a FCC type).

The Pilot Plant was remodeled with the CPERI design, but to the surprise of the team, the Demonstration Unit design was not changed. According to those familiar with the timelines, the Demo Reactor was already fabricated and was soon to be delivered to KiOR for installation, based on the old, obsolete original KiOR Pilot Plant Reactor design.

Eventually, the large Reactor of the Demo Unit, with a 10 ton per day capacity, would have to be dismantled and be replaced by the new Frustum Reactor licensed from CPERI. Resolution of the problem would lead to sensational additional costs and delays in the operation of the Demo Unit.

How could this have happened? As it turns out, Robert Bartek, described by one team member as “the expert who had supervised the Pilot plant testing work at the KBR Pilot Plant after De Deken had left, who had managed the design and operation of KiOR’ KCR Pilot Plant and who had worked closely with Prof. Vasalos and Dr. Lappas in transferring their Reactor design to KiOR,” was left almost completely out of the loop.

According to KiOR team members of the time, Bartek “was intentionally kept in the dark and out of the design work of the Demo Unit until almost to the end of the project.”

Why? Perhaps because Bartek was openly and clearly criticizing the BCC Technology and its Catalyst for being “a failure and useless to KiOR”.

“Suggestions and disagreements were considered to be politically incorrect, and rather blasphemies against the party-line prevailing in 2009, supporting and promoting exclusively the BCC Technology and its Catalyst,” remarked Dennis Stamires, when asked about the crisis. More than one KiOR team member contended that the decision to exclude Bartek from the Demo design process, among other consequences, convinced Bartek to resign.

About NASA syndrome

There are some classic management set-ups that lead to failure, one of which is NASA syndrome. The type of management failures that were prominently on display in the Challenger and Columbia disasters. As the Columbia Accident investigation Board reported:

The organizational causes of this accident are rooted in the space shuttle programs history and culture, including the original compromises that were required to gain approval for the shuttle, subsequent years of resource constraints, fluctuating priorities, schedule pressures, mischaracterization of the shuttle as operational rather than developmental, and lack of an agreed national vision for human space flight. Cultural traits and organizational practices detrimental to safety were allowed to develop, including: reliance on past success as a substitute for sound engineering practices (such as testing to understand why systems were not performing in accordance with requirements); organizational barriers that prevented effective communication of critical safety information and stifled professional differences of opinion; lack of integrated management across program elements; and the evolution of an informal chain of command and decision-making processes that operated outside the organizations rules.

Finally, the Board noted:

The pressure of maintaining the flight schedule created a management atmosphere that increasingly accepted less-than-specification performance of various components and systems, on the grounds that such deviations had not interfered with the success of previous flights.

The NASA cautionary tale is instructive; there are correlations between KiOR and Columbia.

Specifically, reluctance to test to understand why systems were not performing in accordance with requirements, organizational barriers that prevented effective communication of critical information and stifled professional differences of opinion; lack of integrated management across program elements; and the evolution of an informal chain of command and decision

-making processes that operated outside the organization’s rules.

KiOR was on a fast-paced commercialization track, as it highlighted in this company slide presentation.

Never commercially viable?

The technology’s progress was under close scrutiny by February 2010, when it was decided to form a Diligence Team consisting of Prof. Vasalos and Dr. Stephen McGovern, a hydroprocessing expert. The review included data and related information derived from KiOR’s R&D work, as well from literature including patents, and data from the CPERI Pilot plant.

By this time, concerns about the data stream from the pilot also became an issue within the company. Stamires himself recalls six such meetings with CEO Fred Cannon, on February 10, March 13, March 26, April 28, May 7, and May 12. What was Stamires bothered about? Specifically, “manipulation and inflation of the pilot plant Bio oil yield data.”

The results of this comprehensive and in-depth Technology Assessment Review Study by Vasalos and McGovern were published in April 2010. Flat out, the report contained the most dismal news possible. The assessment concluded that the maximum yield, based on the pilot plant, was in the low 40s with 15% oxygen content, using ZSM catalysts.

Recommendations were made for improvement. According to one familiar with the report, by and large, these recommendations “were ignored by the Management Team, and not implemented.”

The Impending Public Statement on the Technology

Meanwhile, there was pressure on the company to make disclosures regarding the company’s progress towards scale, and the yields it was achieving, Specifically, there was pressure on regarding a statement describing KiOR’s technology that could be placed at the KiOR Website and also to be given to the public and potential investors.

Dennis Stamires confirmed that there was a controversy. He himself sent an April 5th memo to CEO Fred Cannon and VP Technology Dan Strope, calling for only “Credible” information only to be released. “The message in the event of being Legally challenged, it should be defendable.” He did not receive a response, he said.

On April 10th, a draft Technology Statement to be posted on the KiOR Website, prepared by Matt Hargarten of Dig Communications, was circulated by Andre Ditsch. It would not reach some members of the scientific team until as late as May 11th.

An uproar ensued regarding the draft statement. Bottom line, there were heavy complaints about false claims, misleading information and fake terms like “KiOR’s Proprietary Magic Catalyst“. CFO Kevin Denicola indicated to team members that he too had serious concerns about the truthfulness of the proposed Technology Statement.

Inflated Numbers: The July 2010 Report

In May 2010, John Hacskaylo joined KiOR as VP R&D. With Cannon and Ditsch, they formed what was described to The Digest as “The Troika, [which] manages all the important issues and business items of KIOR”.

The issues? These would grow to include:

The negotiations with the Mississippi Authority regarding a loan of $75 million; negotiations with Chevron / Catchlight regarding the formation of a joint venture; the Technology Review/ Assessment by R.W. Beck; the Application to DOE for a $1 billion Loan guarantee; the preparation of the KiOR S-1 Prospectus for a NASDAQ IPO; negotiations with potential investors, and updates on KiOR’ s technological progress.

One team member wrote of this time:

The formation of “The Troika” caused a deep division and disputes among KiOR’s managers, which later on dripped down to lower levels of operations, and prevented normal working business communications among employees. Hacskaylo created and highly promoted this culture. R&D personnel were told to whom they can talk and to whom should not talk about their work. Co-operation, trust and willingness to communicate fast disappeared, and a spirit of fear of being punished and fired prevailed in the organization.”

In a July 2010 Report, entitled “Yield Improvement Efforts”, according to those familiar with the report, Hacskaylo replotted the previous Pilot plant data to show a steady substantial oil yield increase in the period of 2009 – 2010, claiming that the Pilot was 50% ahead of the Vasalos report’s findings, in gallons per dried ton of Biomass feed and projecting an 80% increase in yield from the upcoming Demo Plant, or 72 gallons per ton.

The yields, according to key members of the science team, were simply not true, and incredibly inflated. The results were inflated from the latest pilot data. Further, the Demo plant as designed at this time did not incorporate improvements that KiOR had deployed at the pilot.

As one observer noted, “Hacskaylo’s new, much greater inflated oil yields, generously met and even exceeded the milestones which earlier Ditsch, Kaul, and Khosla had set forth to be accomplished quarterly for the year 2010, by the R&D group. Hacskaylo managed to accomplish (on paper only) the [required] milestones of increased Bio-oil yields”, without the bother of actually improving the process, so went the theory.

It is not known whether financial motives, data confusion, or honest mistakes went into the July report or into the criticism thereof. It can be noted that executives of KiOR were rewarded with stock options for meeting milestones and accomplishing goals, but there’s no direct evidence that data was changed for monetary gain. It is clear however that the new data was not supported by those familiar with the raw data coming from the pilot plant. The Digest has obtained and carefully reviewed original data from the pilot from this period and the July 2010 report, and can confirm that the raw data and the July 2010 report do not agree.

Another report was made to Khosla in November 2010, and again team members say that the data was “corrected” and the yields “improved” from actual KiOR data. We are all left to guess exactly why.

At this stage, Denicola is reported to have attempted “professionally…to correct this problem and give the public and investors a truthful and representative account of the actual status of KiOR’s technology at that time,” according to one team member familiar with his efforts, but he was unsuccessful. Denicola subsequently resigned.

Bleak refinery upgrading report and a “see ya later” from Catchlight

In May 2010, samples that had been provided from the KiOR Pilot were the subject of a report from Catchlight Energy, the Chevron /Weyerhaeuser Joint Venture. Catchlight reported on two samples, one containing 11% oxygen content and one containing 17%. Their conclusion: they couldn’t effectively process either sample. O’Connor told The Digest that Exxon also reported trouble.

They did indicate that they believed that, with time, a process could be found that would tolerate the 11% oxygen content sample, though it would require alternative equipment that Catchlight was not in a position to finance. They further indicated that the 17% oxygen content bio-oil could not be processed by any existing refinery plant hydroprocessing equipment, and that new technology would have to be developed from the ground up, for that.

Either way, the idea of delivering a bio-oil to Catchlight was out. Catchlight indicated that, going forward, they would only be interested in handling a finished fuel blendstock that had been hydroprocessed by KiOR. Whether that meant using standard or modified equipment, or

developing a new technology, would be up to KiOR and at KiOR’s expense.

KiOR does not disclose Catchlight Energy’s deep reservations in this slide deck overview given in 2013.

Selling it to Mississippi

“By mid-June 2010,” as the state of Mississippi recounts in its lawsuit, “Khosla Ventures had retained Dennis Cuneo to assist KiOR in obtaining a favorable state economic development package. Cuneo is a former Toyota executive who enjoyed valuable relationships with Governors of southern states. Cuneo quickly arranged meetings for KiOR and Khosla with the governors of Arkansas, Louisiana and Mississippi. The first executive level meeting between the State of Mississippi and KiOR occurred on July 1, 2010 at the office of Governor Haley Barbour. Three entities were present at the meeting: KiOR, Khosla Ventures and the State. KiOR was represented by Fred Cannon, Mike McCollum (KiOR’s Vice President of Supply) and Andre Ditsch. Khosla Ventures was represented by Vinod Khosla, Samir Kaul and David Mann. Also present for Khosla Ventures was Dennis Cuneo. The State was represented by Governor Barbour and two MDA officials, Adam Murray (MDA Project Manager) and Justyn Dixon.”

Among the documents providing support for the meeting’s agenda was “An Overview of KiOR in Mississippi” white paper, provided to the Mississippi Development Authority, which made the following claims:

1. “Existing refining infrastructure can easily upgrade the oil into transportation fuels, making KiOR’s oil a direct substitute for imported crude oil without changing the refining to automobiles supply chain and infrastructure.”

2. “Our product is a high quality crude oil that can be converted into on-spec gasoline, diesel and jet fuel with standard equipment in operation in every US refinery.”

3. “Our process is already competitive with oil at $50/barrel with existing subsidies, and will be competitive with $50/barrel oil without tax credits in 2-3 years with catalyst tuning and process development, allowing economical access to nearly all available feedstock.”

The state of Mississippi alleges that the financial information provided to the state “did not account for the construction and operation of a hydrotreater and hydrogen plant at the Columbus facility.”

At the time, KiOR may have well held out hopes that a hydrogen plant could be built in partnership with a vendor, who would pay for construction and operation and charge a hydrogen delivery fee to the project. However, given the July 2010 date of the initial Mississippi meeting, there is no doubt on the Catchlight score. At best, KiOR may have believed that other refiners would be able to process its bio-oil.

Did KIOR include water in its bio-oil yield claims?

KiOR’s assertion that the technology “is already competitive with oil at $50/barrel with existing subsidies” seems remarkably similar to the speculative analysis completed by Andre Ditsch at the time of the UOP/PNNL paper, based on 65 gallon per ton yields. There is no documentation that The Digest has been able to uncover, nor any scientist we have interviewed familiar with the actual data out of the pilot plant, that supports KIOR yields at breakeven points.

A KiOR staffer relates a tale about André Ditsch. “Suppose you had a restaurant that seated 200 people,” Ditsch is reported to have told a KIOR team member, when questioned about the reporting of the KiOR numbers. “And, you only seated 10 today, but you were going to seat all 200 in the future. If you say that you are at 100% occupancy, that’s not misleading, because you are going to be at 100% eventually.”

The truth may well be that the KiOR yield claims were based around liquids, rather than bio-oil, coming out of the process.

The state of Mississippi alleges just that. Specifically, that:

“Ditsch’s failure to accurately adjust for losses to water and other waste products also rendered the representations to Mississippi officials false. When the BCC reactor was operated at high oxygen levels (greater than 10%), a substantial percentage – more than 30% – of the biocrude produced by the BCC reactor was lost to water.

“Ditsch’s failure to make an appropriate reduction for losses to water served to substantially inflate his yield estimate; and, as a consequence, the Company’s financial projections misleadingly made the Company appear commercially viable. Neither KiOR nor Khosla nor Cuneo notified Mississippi officials that the Company’s financial projections were grossly inflated to overstated yields.”

Paul O’Connor, as a member of the KiOR board, has a similar theory.

“Hacskaylo, what a disaster area. The 67 gallon figure, that is where I became suspicious. The board hardly saw technical information, as you can imagine people like Condoleezza Rice were not going to be very familiar with technical detail. They were showing us graphs with yields of 68-72 gallons per ton out of the pilot, and they aid that the demo plant was even better. Now my initial reaction was you’ve got 100 people working in R&D, you’ve got all the best equipment in the world, you’ve figured it out, that’s great.

“But one day I noticed the R&D director, John Hacskaylo fiddling around with the axis, and in his comments to us, he was talking about top of the reactor yield.

“Top of the reactor? That’s the yield coming out of the pyrolysis unit, but that is not the yield coming out of the plant. You have to condense, and you have to recover oil from water, and you lose in the hydrotreater, because for one thing you have to take out oxygen. It’s not a real yield coming out of the plant.

Top of the reactor yields, in the context of transportation fuels, is like counting scotch and water as pure scotch whiskey. Or including the weight of the orange peel in a projection of orange juice yields.

“If you’re saying 68 at the top of the reactor, at best you are making 55 in the plant. At best. So that’s when I insisted on a technology audit,” O’Connor told The Digest. “It was definitely not at 68-72. There were some points where you could get above 60 but only momentarily, under ideal conditions, for instance with very fresh catalyst. And only in the pilot.” O’Connor confirmed that the demo plant was generating yields in the 30s or low 40s at most.

“Who did the analysis? Were they just stupid or crooks?” O’Connor asked. “It’s not for me to say.”

A company on the brink

The company was speeding towards a 2011 IPO. But the fuel yields were low; the fuel was not usable by their initial chosen downstream partner; the catalyst they were using to get even down to this unsatisfactory product, ZSM zeolite, was in the $7,000 per ton range. Catalyst stability would be challenged, everyone knew, with the water that is contained in wood chips. Steam can be highly problematic for zeolite.

More than that, the company was facing a potential problem with the metal content in the biomass feed that accelerated the deactivation rate of the catalyst, which resulted in excessive amount of daily catalyst replacement, according to one KiOR scientist.

There were reactor design issues. The pilot reactor that was working wasn’t used for the demo unit.

There was a rush to commercial-scale of the NASA type. Management issues, communications

issues can be seen. Disclosure issues, “truth in data” issues. And, a series of statements to the state of Mississippi that would be impossible to live up to without major improvement in yield. Capital needs were going to be tremendous, and beyond an IPO there was a loan guarantee process and the state of Mississippi loan application to be successfully navigated.

Why the rush to scale? All venture-backed companies rush. But was there a special rush on with Khosla-backed companies, and did that rush apply successfully to industrial technology? The State of Mississippi quoted this passage from the Harvard Business School case study, Khosla Ventures: Biofuels Gain Liquidity:

“Khosla played an active role in helping his portfolio companies determine appropriate milestones in the process of moving from a pilot to a commercial operation. He encouraged his companies to focus on 15-month or 15-day or 15-hour innovation cycles, unlike the 15-year cycles of innovation in the nuclear business, in order to “test, modify, allow lots of mistakes and still succeed.”

The goal was to test ideas in 10% of the time that it would take a large company. Once that was achieved he often challenged the team to reach another 10x reduction in cycle time. month or 15-day or 15-hour innovation cycles, unlike the 15-year cycles of innovation in the nuclear business, in order to “test, modify, allow lots of mistakes and still succeed.”

Everyone was counting on everything to improve in the demo unit, and in 2011. As sometimes happens. And, with design corrections, fingers crossed this could be translated to a commercial-scale unit. It’s been known to happen, yields improving as scale increases and design improves. Not always, not often, but sometimes. Could KiOR pull it off?

Maybe, just maybe.

KiOR was hanging by a thread as the summer of 2010 commenced. In a few days, the first recorded visitors to Pasadena demo unit, representatives of the Mississippi Development Authority, were expecting to see the demonstration unit in action.

We’ll see how all those concerns worked out in the next part of our series, as KiOR launched its demonstration unit, geared up for more financing and an IPO, and hurtled towards commercial-scale.

Further reading.

The O’Connor resignation letter

The March 15 2012 O’Connor email memo

The March 22 2012 O’Connor technology assessment

The April 21 2012 O’Connor technology assessment

The April 30 2012 O’Connor memo

The Spring 2013 O’Connor note

Jim Lane is editor and publisher of Biofuels Digest where this article was originally published. Biofuels Digest is the most widely read Biofuels daily read by 14,000+ organizations. Subscribe here.