Tom Konrad CFA

Comverge (COMV) has a great residential demand response business. The company lacks focus, but the stock has significant upside as an acquisition target.

As part of my ongoing series on energy management companies (see these articles on World Energy Solutions (XWES) and EnerNOC (ENOC)) I spoke with Comverge CEO Blake Young.

The Comverge Advantage

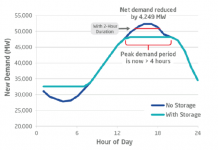

Comverge is the strong leader in residential demand response (DR,) one of the most cost effective grid stability solutions. Even within demand response, residential DR is an excellent niche, because working in the market for residential DR is much more difficult than for that commercial and industrial (C&I) DR. For instance, World Energy Solutions CEO Rich Domaleski told me that his company leverages their market based energy sourcing platform to sell the other energy services, such as efficiency and DR. Yet World Energy has no interest in entering the residential space: their focus is on large customers where they can make a significant profit from a single transaction, and they typically only consider customers with annual energy budgets over $500,000, or more than 100 times a typical household energy budget. DR leader EnerNOC likewise focuses on large C&I customers for similar reasons.

Yet there is strong demand for Residential DR as well. Although it’s cheaper to achieve large reductions in peak demand at large electricity customers, many utility regulators have a mandate to allow all classes of customers to participate in utility programs. In practice, this means that many utilities will pay more per MW for residential DR than they will for C&I DR, leading to higher margins for those companies able to provide residential DR cost competitively. According to Young, Comverge ended 2010 with 41% gross margins on their residential business (57% of sales), but only 33% gross margins on their C&I business (43% of sales.)

In residential DR, Comverge places a switch and transmitter/receiver on mainly air conditioners and pool pumps, gathering DR capacity a kilowatt at a time. It takes 1000 houses to get 1MW. In commercial applications, one single steel mill’s DR capacity could be 50MW, the equivalent of 50,000 houses. Residential is harder to deploy, but once deployed, it is distributed and easily cycled. Commercial is bigger, but the DR company needs to deal with professional energy managers who are liable to shop around for the best deal, compressing margins. And just like distributed generation, distributed DR has advantages for utilities in that they can address local stresses on the grid with local demand reduction.

Comverge’s expertise in Residential DR grew out of 30 years of history selling equipment to utilities used in DR programs. They launched their program to provide Demand Response as a service in 2003, and went public in 2007. They’ve been able to achieve their leadership as a residential DR provider because they have a large number of scalable residential DR contracts.

The Stock Price

Given Comverge’s leadership in the highest margin DR niche, it is rather surprising that the stock has performed so horribly since Young took the reins in February last year. When I asked him to what he attributed the fall in the stock price, he told me that Comverge has “trended virtually the same as other companies in the space.”

A quick look at the graph below will show you that that is an overly charitable description of the stock’s performance, at best. The only other pure-play DR company is EnerNOC, and while the two companies followed the same trends closely from their IPOs in mid 2007, a significant gap has opened up over the last two years.

Since February 2010, EnerNOC shareholders have lost roughly half of their money, while Comverge shareholders have lost three-quarters of their investment. If Young believes Comverge has trended “virtually the same as other companies in the space” during his tenure, he must consider Comverge’s “space” to be companies in severe financial trouble.

Fear of Dilution

Comverge is not yet in severe financial trouble, so why has Comverge fallen to the level reached only in the depths of the 2008 financial crisis? The answer, most likely, is shareholders’ fear of further dilutive offerings. Selling new stock to raise money is not always bad, but it is a problem if shareholders think it will be invested in less profitable businesses than the current one.

Young’s apparent complacency about the stock price seems to extend to a general complacency about the use of shareholder funds.

Where does the capital go? Young gave me the example of the recent PJM (a regional electricity transmission organization in the Eastern US) auction for the 2014-15 capacity year. Comverge bid for and won 20% more capacity in that auction than they won in the 2013-14 auction. Meanwhile, the market is becoming more competitive, with prices in the PJM auction having fallen 20% over the previous year, meaning that Comverge’s expected revenue from the PJM market will be 4% lower in the 2013-14 year than in 2012-13, while they have to acquire 20% more MW. Growth is good, but in this market Comverge is running just to stand still. Those contracts tie up capital in the form of collateral which will be paid in penalties if Comverge does not meet its obligation to deliver those megawatts. What’s particularly ironic about this is that PJM introduced a new mechanism in this most recent auction to allow smaller players to bid without putting up as much capital, which Comverge did not take advantage of because they consider it too complex.

Comverge has been investing in a lot of things other than what they are best at, which is residential DR. Young told me that the company is aggressively pursuing C&I customers (the C&I share of revenues has been growing much faster than the Residential), as well as investing heavily in their IntelliSource software platform. They recently also moved their former CFO to a newly created position as head of international operations, where Young says they are “looking very hard” at the Middle East, Africa, China, and South America.

While any of these strategies might make sense for a profitable company expecting maturation of its core busin

ess, Comverge is not profitable, and residential DR (as well as DR in general) has plenty of room for growth according to Young himself.

Comverge’s experience with small residential customers might serve to give the company an advantage when working with smaller commercial businesses, but they don’t have any obvious advantage with the large C&I clients, and they are pursuing those as well.

When I asked Young what competitive advantage they have in the C&I market, he spoke of their close relationship with their customers, and IntelliSource, which incorporates large amounts of data about the electricity use and control on the system to better predict how many MW of capacity they can deliver at any time. He also says that many utilities like to work with a single demand response provider. IntelliSource seems like more of an advantage with smaller customers. Large customers’ power usage naturally comes in larger blocks, so such detailed data, while useful, will be less relevant than with large numbers of smaller customers. Yet the argument that utilities like to work with a single provider is a strong one, and justifies Comverge’s presence in all parts of the DR market, even if they do not have a competitive advantage in large C&I.

Yet that argument does not justify the company’s expensive participation in the competitive PJM market, which does not differentiate between DR sourced from residential customers, nor does it justify a move overseas.

What I’d prefer to see is a focus on growing the core business of working with utilities that do want a significant portion of their DR megawatts to come from residential customers, in order to maintain the company’s profit margins at least until Comverge achieves profitability and there is a significant recovery in the stock price, which would lower the company’s cost of funds. Moving into more and more new businesses adds to overhead and moves this date out further and further.

Shareholder Discontent

The plummeting stock price and lack of focus have drawn the attention of a group of activist shareholders called SAVE, led by Brad Tirpak, whose provocative ideas about distributed solar’s effect on utilities I wrote about in February. Comverge’s 2006 S-1 registration statement states that the certificate of incorporation “provide[s] for a classified board of directors, [which] could discourage potential acquisition proposals and could delay or prevent a change of control.” SAVE first needed to remove Comverge’s classified board structure in order to gain influence at Comverge.

Tirpak sponsored a proposal on Comverge’s 2010 Proxy which instructed the board to repeal the classified structure of the board and “complete transition from the current staggered system to 100% annual election of each director in one election cycle unless this is absolutely impossible,” and also requested “that this transition is made solely through direct action of our board if feasible.” The proposal passed with 72% of the vote.

In response, the board placed an amendment to Comverge’s articles of incorporation on Comverge’s 2011 Proxy Statement, which was designed to “implement over a period of three years the stockholder proposal to declassify the Board,” and recommended that shareholders vote for the change.

SAVE saw this proposal as “a thinly veiled attempt to entrench Alec G. Dreyer as the Chairman of the Board for a further three years,” because the board did not declassify through direct action (which would have been immediate) and implemented the proposal over three years, rather than immediately.

The 2010 proposal was clear that legal constraints were the only valid reason not to declassify the board immediately and completely, so I asked frequent AltEnergyStocks contributor and IPO attorney John Petersen and Charles Knight, an attorney with Venture Law Advisors in Denver for their opinions. Both told me that the board would not be able to declassify by direct action and a second vote would be required if the staggered system arose from the firm’s certificate of incorporation, which Comverge’s S-1 confirms is the case. Knight also told me that companies often declassify “over time as the prior directors were elected for longer terms and are generally entitled to serve out their remaining terms if elected prior to declassification under a company’s bylaws.”

In other words, declassification over a period of three years, although slow, was declassification “in the most expeditious manner possible, in compliance with applicable law, to adopt annual election of each director.” Possibly the board could have called a special election of shareholders to declassify the board in 2010, shortly after the shareholder proposal passed, but that possibility was ruled out by the text of the 2010 proxy, which stated that the proposal would run on the 2011 ballot.

SAVE was successful in defeating the 2011 proposal to declassify the board over three years, urging the board to declassify immediately and “explore all strategic alternatives” (i.e. put the company up for sale.) But this was a Pyrrhic victory, as the board cannot legally declassify immediately.

By lobbying against the implementation of its own proposal, SAVE has damaged their own credibility, which makes management less likely to listen to them regarding potential mergers with other companies which might lower Comverge’s cost of funds and produce an immediate return for Comverge’s shareholders. In our interview, Young was quite dismissive of SAVE and Tirpak, whom he seems to regard as minor annoyances.

Value

Although I understand management’s dismissal of Tirpak’s efforts, I also agree that there would be significant benefit to shareholders in the company pursuing all strategic options.

Despite the lack of focus, Comverge has significant value, and at current prices would make an attractive takeover target for other companies in the space. There is a clear appetite from large players for companies in the Energy Management space. For instance, Johnson Controls (JCI) recently purchased the formerly OTC-listed EnergyConnect. These companies have a lower cost of capital, and so can more easily afford the capital needed to participate in the DR space for large customers.

On measures of cash and current assets, Comverge appears well-capitalized, but much of this money is tied up as collateral. The most recent quarterly report states that Comverge committed $17.9M in advance of the 2014-15 auction, funded from cash on hand and a revolver loan. Young told me that they got “some” of th

is back after the auction, so call it $15M. But Comverge’s most recent balance sheet shows less than $27M in cash and $24M debt. Was that a good use of so much of the company’s liquidity?

Yet the company does have a strong backlog, including $532 million worth of future revenues through 2024 under existing long term contracts, and a contractual backlog for the coming year of $128 million as of the end of Q1. At 35-40% gross margins, that’s about $50M per year before overhead costs, but at $3.30 a share, Comverge’s market cap is only $82 million. Comverge would be worth a lot more to an acquiring company like Johnson Controls, or Siemens (SI), or ABB, Ltd. (ABB) that have strong balance sheets and have shown appetites for acquisitions in the smart grid space. EnerNOC, which is profitable, could also see instant gains by eliminating much redundant overhead and gaining valuable expertise in the residential market.

Comverge Should Merge

At the current price of $3.22, Comverge is an attractive acquisition target, and would probably have $6-$8 worth of value to a better capitalized acquirer. But investors who buy now are taking a real risk. Although Young told me that he intends to break even in 2012, such predictions have an unfortunate habit of slipping, and have slipped at Comverge in the past. The company seems to be aggressively investing in less profitable businesses that diverge from its main business and are not justified given Comverge’s current high cost of funds resulting from the lack of profitability and the low share price.

Perhaps Comverge will achieve break-even in 2012 and profitability in 2013, as Young expects. But I don’t see how that will happen without either further diluting existing shareholders, or merging with a larger company that has a lower cost of capital. Since Young and many of the board members are significant shareholders, I hope they see that it’s too their own benefit to take the latter course.

DISCLOSURE: Long COMV, ENOC, JCI.

DISCLAIMER: Past performance is not a guarantee or a reliable indicator of future results. This article contains the current opinions of the author and such opinions are subject to change without notice. This article has been distributed for informational purposes only. Forecasts, estimates, and certain information contained herein should not be considered as investment advice or a recommendation of any particular security, strategy or investment product. Information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but not guaranteed.